Austin Rents Drop Following Construction Boom

Although the most recent CPI report shows shelter inflation, which includes both homes-for-purchase and units-for-rent, continuing to rise at a brisk year-over-year pace of 5.7%, rents in certain markets are actually on the decline. The Wall Street Journal had a piece this week highlighting Austin, Texas, which had been one of the hottest real estate markets in the country for much of the pandemic and the immediate aftermath. But now? The Austin real estate market appears to be in some peril:

[Austin] is contending with a glut of luxury apartment buildings. Landlords are offering weeks of free rent and other concessions to fill empty units. More single-family homes are selling at a loss. Empty office space is also piling up downtown, and hundreds of Google employees who were meant to occupy an entire 35-story office tower built almost two years ago still have no move-in date.

It would be easy to say the pendulum has just swung back on Austin due to the normal ebbs and flows of time after a robust decade of growth. Certainly some of the work-from-home population flow to places like Austin out of the big tech centers and urban areas in the West and Northeast has decelerated. But a major reason why rents and home prices are dropping in Austin is because there has been so much construction of new units over the past few years. Although the tone of The Wall Street Journal article is dour, this is a success story (at least from the perspective of tenants; landlords, property owners, and local Austinites concerned about growth and sprawl might say otherwise).

The Impacts of Total New Apartment Supply

In January, John Burns Research & Consulting published a report documenting what it calls “Total New Apartment Supply.” This statistic is simply the sum of the completed rental units in the last year and the units currently under construction. This provides a handy way to see how much new rental supply is coming online within a 2-3+ year range combining both the completed units and the ones that will be finished in the months ahead.

So what’s going on in Austin? Well, the Texas capital ranks #4 on the list of Total New Apartment Supply with 17,025 units completed in 2023 and a whopping 42,986 units newly under construction for a total of just over 50,000 new units. That’s a lot of new units even for a metro area as large as that of Austin.

What about rents? According to data from Apartments.com, the average rent in Austin is $1,439/month, which is down $105/month in the last year or about 7%. And it seems that the rate of decline in rents is accelerating: according to Rent.com data (via the Austin-American Statesmen), rents in December 2023 in Austin were a whopping 12.5% lower than the previous December. This decline was the second sharpest of any metro area in the country.

If You Build It, Will the Rents Drop?

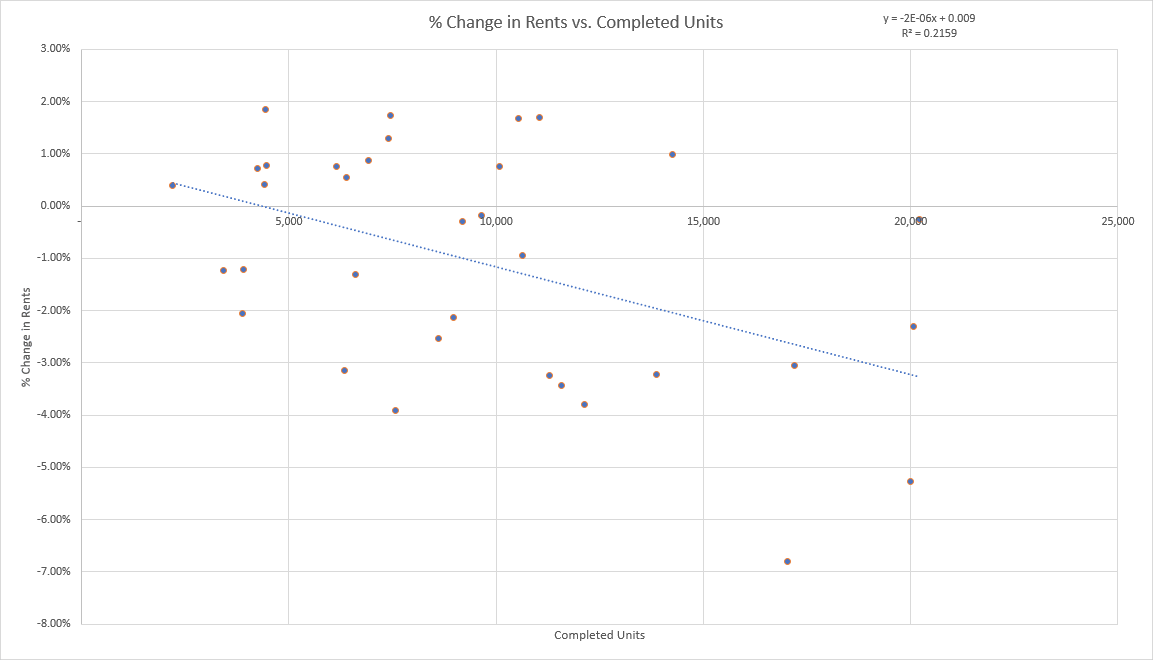

The Austin Experience has major implications for the rental market nationwide. With that in mind, I thought it would be worth looking at the other metro areas in the John Burns report to see if the correlations between Total New Apartment Supply and rents (at least per the Apartments.com data) hold true for other areas. The chart below is a statistical analysis my Sunday Morning Post intern Ford Smiley put together showing the percentage change in rents over the past 12 month (vertical Y-Axis) with the number of new units completed in the past year (horizontal X-Axis). As you can see, there is some visible correlation: as the number of new completed rental units increases, rents have fallen.

Keep in mind that this is only a partial dataset; it only is looking at the metro areas in the John Burns report, which were all noted as communities in which there was strong Total New Apartment Supply. A full and better analysis would also look at data from a broader list of communities including smaller ones and ones, in particular, that do not perform as well in the Total New Apartment Supply dataset. I’d like to come back to that in a future article after obtaining some broader and more detailed data. But the implications of the trend line above are pretty significant.

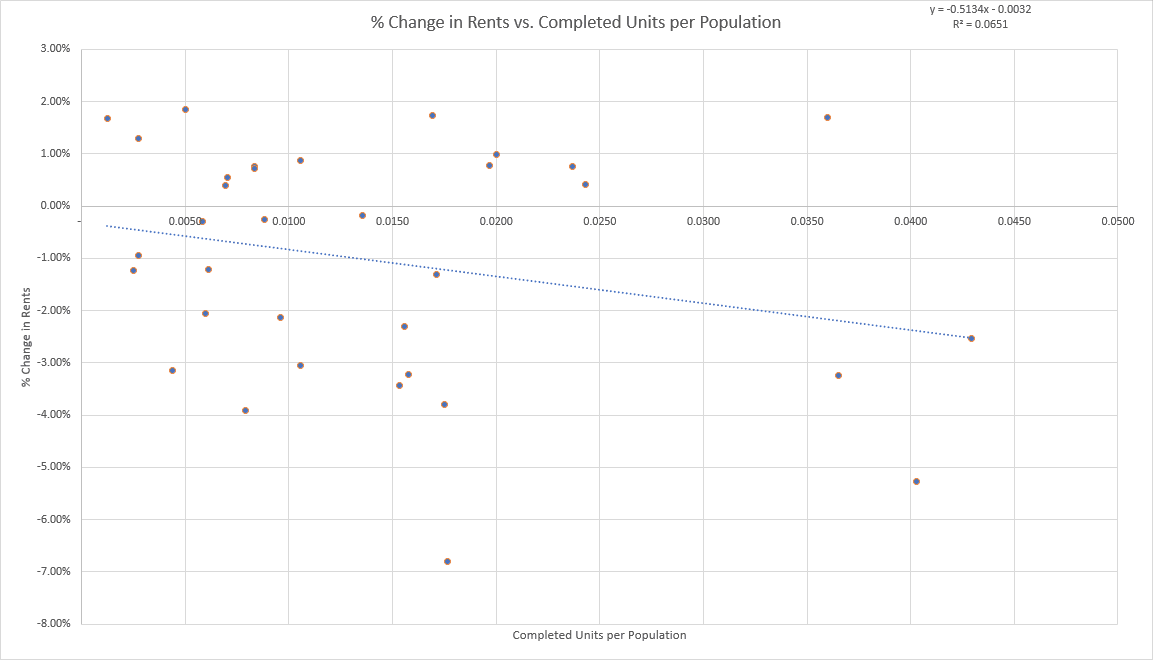

Below is a similar chart using the same basic data set, but the X-Axis is the number of new units completed divided by the population of the city. This is probably a better metric to look at because the impact of a single new rental unit in a place like Boston, for example, is going to be less than the impact of a new unit in Bangor, Maine. Although, as noted above, it is important to keep in mind that this dataset is pretty much all fairly large metro areas. I thought it was important to show this chart as well, though, which shows the same trend as the above chart although at a little bit of a more shallow trajectory.

What Comes Next

The story in Austin should be on the mind of policymakers across the country as they ponder how to decrease rents. As construction of new units increases, rents decline.

I think, too, that returning to this dataset year after year will show more statistical correlation. There are lag effects at play because rents do not fluctuate daily or weekly the same way the price of, say, orange juice does at the grocery store. Rent changes only really get realized for the most part upon lease renewal, renegotiation, or tenant turnover. My guess is that in overheated housing markets like Austin, leverage in lease pricing is switching from landlords to tenants. As tenants absorb the implications of all of this new supply, they will either negotiation harder for rent reductions (or at least to hold rents level upon lease renewal) or will leave their existing units to test the market and find a better deal. Once that unit then becomes vacant, landlords will have to re-price to meet the market where it is, which could lead to more systematic declines in rents as these waves of re-pricing hit the statistics. Since leases are generally only re-priced once a year, it will take some time for the impacts to show. I predict the trend line in the charts above will be steeper a year from now when not only more units have come online, but changes to rents due to normal turnover have been realized.

Will the Pendulum Re-Swing?

I’ve mentioned a few times in these articles how it is unfortunate that at a time when the housing crunch has been the most acute, it has become so difficult to build. This applies to both residential home loans and commercial loans for construction of rentals. The major impediment at the moment is the high cost of borrowing because of high interest rates. Many multiunit rental projects just simply do not cash flow at these high interest rates, so they are getting pulled off the table and either delayed or outright cancelled. At a certain point is just a question of math. Multiunit rental permits for construction are down sharply, which means that after the current glut of new supply all comes online (much of which is still actively under construction now), things may decelerate a bit. Time will tell.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

Weekly Round-Up

Here is what caught my eye around the internet this week:

In researching what people from Austin are called for today’s article (Austinites), I found reference to people who were born in Austin calling themselves unicorns because it is so rare to find someone in Austin who was actually born there.

How do you foster community among a remote workforce? It’s an important question with so many jobs now offering a work-from-home option. It’s also particularly important in this era of declining civic participation, which I wrote about a couple years ago in Still Bowling Alone. Rachel Montañez had an interesting piece in Harvard Business Review on the topic entitled, “Fighting Loneliness on Remote Teams.” You can read it here.

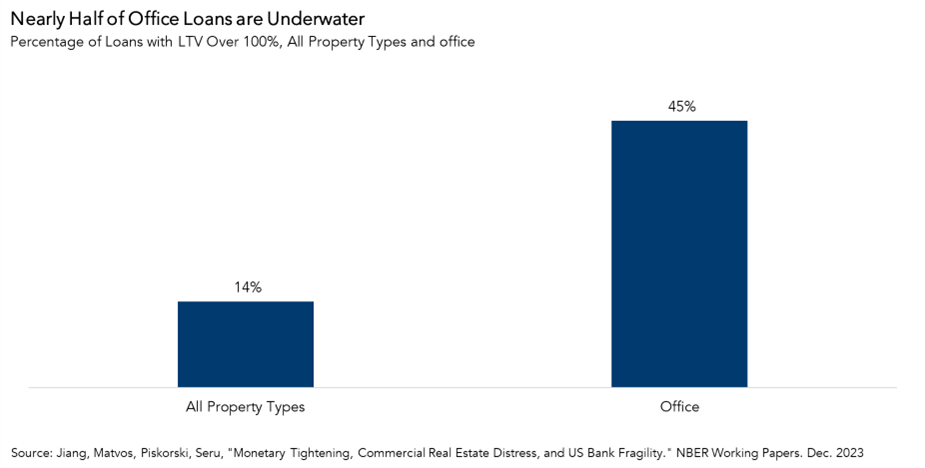

Almost half of office building loans are underwater right now from a loan-to-value perspective. What that means it the properties are worth less than the loan balance. How did this happen? Well, the banks lent perhaps 80% of the building’s value at the time of origination, but the values of these properties have declined by so much in the last few years that the loan balances are now higher than the property values. Read more via Xander Snyder, including further discussion of the chart below:

One Good Long Read

By Sarah McDermott of the BBC, “The guitarist who saved hundreds of people on a sinking cruise liner.” This piece is a fascinating look at the sinking of the luxury liner Oceanos off the coast of South Africa in 1991. I won’t spoil the story here, other than to share this one bit of dialogue:

Moss had no idea what their coordinates were.

“What rank are you?"

"Well, I'm not a rank - I'm a guitarist."

A moment's silence.

"What are you doing on the bridge?"

"Well, there's nobody else here."

"Who's on the bridge with you?"

"It's me, my wife - the bass player, we've got a magician here…'"

You can read the full piece here.

Have a great week, everybody!